Explore “Mining the Museum” in terms of “difference”.

“It would be an error to think that difference was the only thing a work had to offer. However, with some caution and a little license, we can show that some works invite a differential interpretation more than others.” (Visual Studies 1: Understanding Visual Culture course manual p111).

This study will take Fred Wilson’s Baltimore exhibition “Mining the Museum” (1992-3) as the basis for an examination of possible interpretations of difference.

In 1969, Ayn Rand stated in “Art and Cognition” that “art is a selective recreation of reality according to an artist’s metaphysical value judgements” (atlassociety.org). This “selective recreation of reality” can be viewed in any museum, because what the observer sees, is only what the curators have chosen to place on-view. This difference is a very metaphysical one: one person’s experience of reality is greatly different from the next. In “Mining the Museum” (1992-3), Wilson juxtaposed objects from the Maryland Historical Society’s reserve collection with objects on permanent display to highlight these differences. The study will examine these in terms of both material and metaphysical difference, and will also touch on other artists who have worked in similar ways.

It is by nature of material difference, that objects tend to find their way into museums; there needs to be some kind of intrinsic interest appealing to the potential observer. The ways in which museum objects are placed on view (and therefore these differences are communicated to the public) are curator-driven. As places of education, these subtle communications are thus taken as fact. As Marcia Pointon reminds us, “it is important on entering any institution that displays visual culture to remind ourselves that what we are seeing is not a natural selection but a carefully orchestrated arrangement which results from a series of decisions” (1997, p8). Often, these decisions are subconscious ones, revealing much about what is excluded as much as what is included.

On graduating from Art School, Wilson’s tutor asked him if he wanted to belong to the white art world, or the black one. During the four years he had spent there, nobody had suggested that there may be two choices. This became apparent once Wilson got work as a curator: in art and artifact museums alike, and he began to get a sense of how objects were displayed. In his words:

I began to have ideas about (museum) environments… essentially at that time, it was just white Americans creating the meaning… I don’t think they- museum people- were trying not to include us in the conversation, it’s just that they didn’t realise they weren’t including us (Fred Wilson’s Museum Intervention, 2019).

Museums hold the beauty of one’s culture and another museum the horrors of our culture, but never in the same display case. But- whose hand served the silver? Who could have made these things in apprenticeship situations? Whose labor supported the wealth that produced this silver?… I’m really interested in how you juxtapose a thing with another thing- a whole new thought comes about (The Backlash of the Fred Wilson Project, 2013).

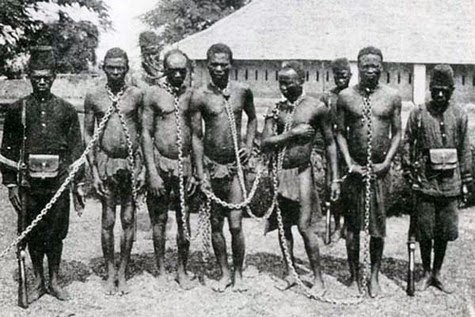

Wilson sees himself very much as an artist, not as a curator (Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum 2011), and “Mining the Museum” was an entire exhibition, not one isolated piece of art. Its purpose was to show, through careful juxtapositions of objects, that museum display could incur different trains of thought: Wilson was thus able to “illustrate the way in which many unpleasant aspects of social history have been conveniently overlooked by the intitution” (Putnam 2001 p157). Fig 1 shows the most commonly used example from the exhibition: a vitrine containing high-end silver-ware, in the middle of which have been placed a set of slave-shackles. Both examples of metal-work are local to the area; the silver-ware being on permanent display and the shackles for the most part kept in the Maryland Historical Society’s reserve collection. There are several differences in play between the objects in this case.

Objects in museums are, as already stated, intrinsically different from every day objects. That is why they are in museums, in glass cases, illuminated and kept separate, with little cards telling us what they are. We recognize a jug as a jug, and a goblet as a goblet and a tankard as a tankard: these objects have different uses. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, everybody drank beer, it was cleaner than the water that most people had access to. Most people, however, did not drink their beer from silver tankards, they will have used something much more humble. This is the signifier, this is what marks these vessels as somehow different from the norm, and this is what, in a Saussurian sense is being signified; the high value of these objects- in this museum, at least- is what has gained them their place in the vitrine. Then, the observer notices the shackles. It isn’t obvious at first glance, what these objects are, because we as observers, are not used to seeing these objects. We recognize the shape of jug, goblet, tankard: the high value of the metal used is irrelevant. A goblet could be made from wood, and it would still be a goblet. This is difference, subordinate to identity. It is a technical matter; as Davis (2003, p332-333) comments, ” ‘Difference’ refers to the distinction, even the opposition, of terms or elements (or their properties) in a field of representational possibilities”.

This brings an interesting dimension to the fore. We don’t recognize those dull metal objects really. It is obvious that they have some utilitarian purpose, they are dull iron things, with loops, and some chain, and is that a key? Are they for hanging joints of meat up for curing? Maybe the comment is about what happens in the kitchens of a wealthy house, compared with the luxurious consumption going on in the parlour?

The truth, when we read the label in the vitrine, is an uncomfortable one. The juxtaposition of material difference is the same: dull low-value metal versus bright shiny silver. But the metaphysical difference, the differential: is vastly different.

Differential as a term, is literally “different” from Difference. Take the numbers 8 and 9. They are, literally, different numbers. They represent different amounts of things, the shape of the symbol for each number is different. The differential, the difference between them, is 1. It is the concept which lies between 8 and 9, if you like, the forward slash, the connection or tension between them. It is the differential then, between the shackles and the silver-ware, which is what we are forced to confront once the uncomfortable penny drops and we realize what those iron objects are (Fig 2). This is, as Michael Belshaw suggests, identity subordinate to difference: “The dark-matter of the world.” (2016, p106).

Wilson’s exhibits did not only concern objects kept within vitrines. Another example worth looking at, is “Modes of Transport 1770-1910”, an arrangement of old fashioned prams, a sedan chair and a ship (figs 3 and 4).

The “museum value” of these objects lies less in their value, (they are not, after all, encased in vitrines) but their old-fashioned novelty: the old-fashioned prams bearing more than a passing resemblance to the vehicles of the early twentieth century with the big wire wheels, carriage shaped bassinets and fancy parasols. Older visitors to the museum might just about remember using such equipment. It is only on closer inspection, that the observer will notice a hooded garment in the pram, a Ku Klux Klan robe. There is no mistaking this object, it suggests disturbing associations with the white baby the pram once carried and the black servant who may have pushed it. The idea was reinforced by the display of a photograph showing two black nannies with a very similar pram.

Objects on display in museums are concerned with a certain amount of fetishism. As Emma Barker comments, “by isolating objects for purposes of aesthetic contemplation, it encourages the viewer to project on to them meanings and values that have no real basis in the objects themselves” (1999, p14). In this sense, observers of these objects take in the shape, the unusual wheels, even possibly the musty smell: the objects are the subject of the observer’s gaze. Taken out of context and placed under the museum spotlight, they become akin to objects of worship. The sudden confrontation provided from the unmistakable KKK robe jolts the observer out of their reverie. The experience afforded by this exhibit suddenly changes and the meaning immediately becomes different. Happy nostalgia is transformed into the shock of having to acknowledge the presence of blatant local racism both historic and current: as Wilson comments

(The museum) called me from time to time to discuss things that were going on in the museum and one of the educators called me and said “We have a school group coming in and some of the children are in The Klan. What should we do?” So in case you thought this is just historic, well, no… I basically said, “don’t give out my telephone number”. But this was a really pro-active gesture to bring this exhibition back to this museum who you would never in a million years expect to want to do that.

Rachel Cohen, an artist based in Sussex in the UK, has also utilized notions of difference by placing her own objects alongside vitrines in museums. In 2012, in a collaboration with Brazilian artist Gisel Carriconde Azevedo and Hastings Museum, she placed her own slip-cast boat-shaped vessels into display cases to reflect their contents. Themes were selected to reflect travel, acquisition, craft and materials (rachelcohen.co.uk/rachelcohen.co.uk/re-discoveries.html) and as such, provided an altogether gentler exploration of a sense of gathering: not only of objects into museum cases, but the swapping of knowledge, trade, rescue, nurture. This is difference-subordinate-to-identity, presented in a positive way: it shows what there is, rather than highlighting what there is not.

Another artist who works in tandem with museums is Andrea Fraser, who, since the 1980’s, “has probed the social, institutional, political and economic structures of art through her works and writings” (Gale 2016, p132). As a performance artist, she took on the persona of a museum guide (whom she named Jane Castelton) and became associated with institutional critique following her performance “Museum Highlights, a Gallery Talk” of 1989. In it, she used the typical “museum speak” of the institution to describe the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the funding used to finance it which came from the public purse:

In 1922 the Museum wrote that “we have come to understand that, to rob people of things of the spirit, and to supply them with higher wages as a substitute, is not good policy, good economics or good patriotism”… The Municipal Art Gallery that really served its purpose would provide an opportunity for enjoying the highest privileges of wealth and leisure to all those who had cultivated tastes but not the means of gratifying them. And for those who had not yet cultivated tastes, the museum would provide a training in taste. (Andrea Fraser’s Museum Highlights, a Gallery Talk (excerpt 1989) 2019.

Fraser’s work is more explicit than either Wilson’s or Cohen’s. There is no real “mining” involved, no digging or revealing hidden meanings. Fraser is explicitly “different” from a normal museum guide, in that the institutional criticism she offers is obvious; she says “you could say that all my work is about the repressed fantasies of our field and about the desires produced and pursued through these fantasies” (Gale 2016 p132). While Fraser stands up, and tells it like it is, on behalf of the under-paid and under-priviledged, Wilson’s meanings take a little more digging (literally, mining). Cohen also takes the museum as medium, but her exhibits encourage the observer to think positively and creatively about the contents of cases; about the places those contents can take us all. Both Wilson’s and Fraser’s work is concerned with uncovering and highlighting hidden social aspects of museums, from within the institutional structure.

Conclusion

The title “Mining the Museum” makes a useful framework to conclude with, as it illustrates neatly the types of “difference” involved. There are three different interpretations of the word “mining” to look at.

The most obvious interpretation is the manner in which Wilson delved into the neglected reserve-collections of the museum, literally mining, or digging objects out, to use them in juxtapositions with other objects. The result is that the observer will see the technical, or material difference, between the objects juxtaposed. There has to be some kind of agreement in play, to cause the observer to acknowledge the difference, that is: the shiny silver objects clearly belong to each other in a resemblant group, and the dull iron objects stand out as being different. This kind of difference/resemblance holds little meaning: it merely provides us with information.

A second interpretation of “mining” is that it is a process which releases materials which are turned into different materials: ores become metals, crude oil becomes all manner of things. By removing these minerals from their original contexts they are turned into other things. Their meanings have changed. The anthropologist Gregory Bateson saw this as the point at which “difference” becomes meaningful: that is, at a higher level of enquiry at which it becomes the differential, the hard-to-grasp dark matter, that needs to be explored. Thus it is ideas, thoughts, which lead us to consider why things inherently, or immanently, differ from other things. Wilson’s mined objects have created thoughts and ideas: as Bateson stated “I suggest to you, now, that the word “idea,” in its most elementary sense, is synonymous with “difference”.” (1972, quoted at informationphilosopher.com). By their nature, these are complicated notions to explain, but as Bateson succinctly puts it:

In sum, what has been said amounts to this: that in addition to (and always in conformity with) the familiar physical determinism which characterizes our universe, there is a mental determinism. This mental determinism is in no sense supernatural. Rather it is of the very nature of the macroscopic world that it exhibit mental characteristics. The mental determinism is not transcendent but immanent and is especially complex and evident in those sections of the universe which are alive or which include living things. (ibid)

A third interpretation of “mining” can be seen as one of ownership, of making things “mine”. In this sense, Wilson has claimed a place for African-Americans in the local history of Baltimore, by physically inserting relevant artifacts into the predominantly white American curated displays. In this way, the African-American experience becomes part of the official history as displayed by the Baltimore Historical Society.

George Orwell wrote “He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past” (1990, p37). We can hardly compare present day Baltimore to the dystopian Oceania of 1984, but there is some truth in this. By ignoring the past and the uncomfortable artifacts firmly left in their reserve collection, the Baltimore History Society had omitted many uncomfortable truths.

Bibliography

Books

Barker, E (ed) (1999) Contemporary Cultures of Display Yale/Open University press, London

Belshaw, M (2016) Understanding Visual Culture Course Manual OCA, Barnsley.

Davis, W (2003) Gender in Nelson, RS and Shiff, R Critical Terms for Art History pp 330-344

Foster, H et al (2011) Art Since 1900 Thames & Hudson, London

Gale, M (2016) Tate Modern; The Handbook Tate Publishing, London

Orwell, G (1990) Nineteen Eighty Four Penguin, London

Pointon, M (1997) History of Art, a Student’s Handbook Routledge, London

Putnam, J (2001) Art and Artifact, the Museum as Medium Thames & Hudson, London

On-line

https://atlassociety.org/objectivism/atlas-university/what-is-objectivism/objectivism-101-blog/3365-what-does-objectivism-consider-to-be-art-aesthetics accessed 28 Feb 2020

Ginsberg, E (1993) Case Study- Mining the Museum at https://beautifultrouble.org/case/mining-the-museum/ accessed 22 feb 2020

Gorrin, LG (1993) Mining the Museum, an Installation Confronting History in The Museum Journal vol 36 issue 4 Dec 1993. At https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/101111/j.2151-6952.1993.tb00804.x accessed 22 Feb 2020

https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/bateson/ accessed 1 March 2020

http://www.rachelcohen.co.uk/rachelcohen.co.uk/re-discoveries.html accessed several times in February 2020

https://thetruthinhistoryinitiative.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/slaves-in-chains.jpg accessed 29 Feb 2020

Wilson, F and Halle, H (1993) Mining the Museum in Grand Street no.44, pp151-172. At https://www.jstor.org/stable/25007622 accessed 3 Feb 2020

Yellis, K (1994) Mining the Medium: Criticism and the Museum Educator in Exhibitionist, pp 44-45 At https://www.academia.edu/6820935/Mining_the_Medium_Criticism_and_the_Museum_Educator accessed 22 Feb 2020

Video

Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum (openingmuseums) 2011 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=csFP2YldIoQ accessed 23 Feb 2020

Fred Wilson’s Museum Intervention- San Fransisco Museum of Modern Art 2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T31_hfpSnDc accessed 23 Feb 2020

Fred Wilson on “Degradaria”- San Fransisco Museum of Modern Art 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CKxA-Yw55E accessed 23 Feb2020

The Backlash of the Fred Wilson Project 2013 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGxdiNd-FyY accessed 23 Feb 2020

Andrea Fraser’s Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (excerpt, 1989) 2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f26NY2xciKk accessed 23 Feb 2020

A Change of Heart: Fred Wilson’s Impact on Museums http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/videos/a/video-a-change-of-heart-fred-wilsons-impact-on-museums/ accessed 26 Feb 2020

Featured image of Fred Wilson taken from archivesandcreativepractice.com accessed 29 Feb 2020